Human rights: How the new Criminal Code curbs freedom of expression in Cuba

In the new legislation, the scope to which some misconducts are considered criminal offenses is too broad and ambiguous, using terms such as "provocation", "arbitrary exercise," or "socialist order."

Human rights activists and government opponents have criticized the new Cuban Criminal Code Act approved unanimously on May 15, 2022, arguing that the legislation criminalizes the right to social protest and freedom of expression.

However, Cuban legislators describe the text as "an expression of the humanistic nature of the Revolution" and "the common interests of people, institutions, and society."

The scope of some misconducts considered criminal offenses in the new legislation is too broad and ambiguous. Moreover, the use of terms such as "provocation”, “arbitrary exercise of rights”, or "socialist order" allows for sanctions based on discretionary legal criteria and could be used as a tool for repression against dissidents in Cuba.

Exercise of constitutional rights

One way the new Penal Code restricts freedom of expression is by regulating constitutional rights, given that these represent a legal guarantee for the free practice of those rights.

In particular, article 120.1 criminalizes with sentences of between four and ten years in prison, the "arbitrary exercise" of recognized constitutional rights and freedoms whose purpose includes:

- "To change total or partially, the country's Constitution or the form of government established in it; or,

- "To prevent the country's president, vice-president, or high State and Government officials from carrying out their duties in whole or in part, albeit temporarily."

In other words, if a Cuban citizen exercises the constitutional right to freedom of expression or demonstration (Articles 54 and 56) in an “arbitrary” way, to change the Constitution and jeopardize the normal functioning of the Cuban state and government, she or he could be sentenced to between four and ten years in prison, at the discretion of the judiciary.

The new legislation does not explicitly explain what is understood by "arbitrarily exercising" the rights and freedoms recognized in the Constitution. Nonetheless, the text gives away some clues.

On the issue of "arbitrary exercise of rights," article 202.1 classifies as an offense the conduct of anyone exercising a right (not necessarily a constitutional one) "by himself" rather than relying on competent authorities.

Independent funding

A new criminal offense that did not appear in the previous Penal Code of 1989 has been added now in section V related to "Other Acts against the Security of the State." Article 143, one of the most contentious in the new legislation, states the following:

"Anyone who, acting on their own or representing non-governmental organizations, international institutions, associations, natural or legal person, national or foreign, supports, encourages, finances, provides, receives or holds funds with the purpose of financing activities against the State and its constitutional order, incurs a penalty of imprisonment from four to ten years."

According to the provisions of Chapter II, Section One of the new law, the following are offenses against the constitutional order: "the attempt to modify, through the abuse of guaranteed rights, the Constitution and the system of government, or to prevent high State officials from carrying out their duties."

The said regulation penalizes what officials see as acts against the Cuban government or "its constitutional order", regardless of where the funds come from. Besides, those who accept funds incur a criminal offense, and those who provide them could also be held responsible. However, it is unclear what the phrase "fund activities against the State and its constitutional order" really means.

Civil society groups see the inclusion of this article as the criminalization of independent journalism in Cuba since most of the media outlets independent from the government get support from private or public subsidies donated by taxpayers and readers.

"Offenses against public order" v/s freedom of expression in Cuba

Although the previous Penal Code Act already considers a criminal offense the intention to disturb public order through "cries of alarm, or threats of a common danger" in places with large crowds of people, the new legislation adds the following in Article 263.1:

"Any person who, through acts of violence, intimidation or provocation, violates the rights of others or affects the public order, peace, and tranquility of families, community or society, is liable to imprisonment for six months to two years, or a fine of two hundred to five hundred quotas or both."

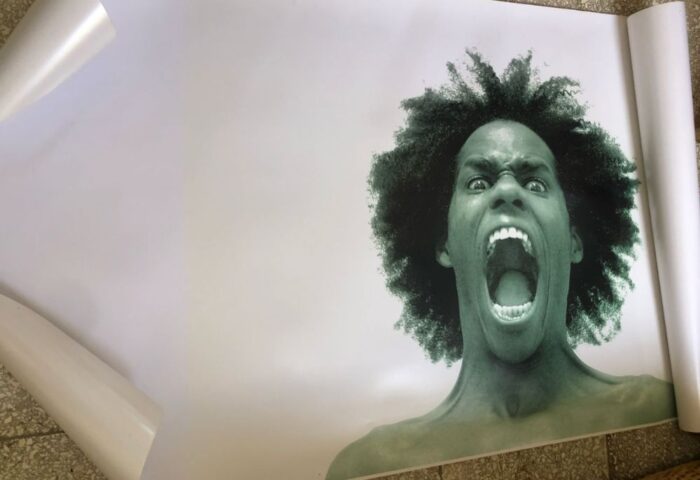

"...the Cuban ruling party has labeled those who have expressed their discontent or exercised their legitimate right to peaceful protest to voice their demands..."

Often the Cuban ruling party has labeled as "provocateurs" those who have expressed their discontent or have exercised their legitimate right to peaceful protest to voice their demands. In light of this, the government could use the new Penal Code to deter people from publicly protesting by threatening them with imprisonment.

In addition, the dissemination of "false news or malicious forecasts to cause alarm and misinformation within the population" is still a crime with up to three years in prison. Lawmakers have added a new circumstance to this section that referred to the intention of "causing public order disturbances."

Similarly, it is still compulsory to obey the orders given by the country's authorities, public officials, and police agents to perform their duties, regardless of citizens' rights.

Telecommunications and Freedom of expression in Cuba

One of the new features in the Criminal Code is the inclusion of the term "social media networks" when referring to certain criminal offenses, such as "instigation to commit a crime, slander, defamation acts against a person's privacy using images, voice, or any other data."

In addition, the new Penal Code considers aggravating circumstances of criminal responsibility the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and telecommunication systems to commit a crime. In other words, the sentence for an offense committed through social media networks would be higher.

According to Giselle Morfi Cruz, a Cubalex lawyer:

"These aggravating circumstances can be used against independent journalists or human rights activists who publicly denounce serious violations to basic rights or criticize the government.”

In addition, the new Penal Code Act imposes restrictions on the universal right to information and its dissemination. For example, article 290 states that "anyone without the proper authorization to access or use a computer system to disclose or disseminate stored information, will be punished with three years in prison."

(This article was originally published by Árbol Invertido as part of its #CUBACHEQUEA project).

▶ Vuela con nosotras

Nuestro proyecto, incluyendo el Observatorio de Género de Alas Tensas (OGAT), y contenidos como este, son el resultado del esfuerzo de muchas personas. Trabajamos de manera independiente en la búsqueda de la verdad, por la igualdad y la justicia social, por la denuncia y la prevención contra toda forma de violencia de género y otras opresiones. Todos nuestros contenidos son de acceso libre y gratuito en Internet. Necesitamos apoyo para poder continuar. Ayúdanos a mantener el vuelo, colabora con una pequeña donación haciendo clic aquí.

(Para cualquier propuesta, sugerencia u otro tipo de colaboración, escríbenos a: contacto@alastensas.com)

Responder